Associate Professor Jenny Ritchie, Victoria University

At a recent event at Victoria University, high school and university student speakers highlighted the need for civics education to be a core subject in our schools, so that young people are better prepared to critically analyse their political options and thus enhance their likelihood of participating in our democracy. Statistics were provided about the low numbers of younger voters.

Every election year I do an exercise with my class of university students who are in the third year of their early childhood education (ECE) degree. I start by asking how many of them are planning to vote, and if so, how will they decide which party deserves their vote. The proportion of students who intend to vote is usually dispiritingly low, and the basis on which they are likely to vote even more so. For example, ‘I will just vote for the same party my parents vote for’ is a very common response.

In the first part of the class focusing on election choices, students compile from their recent research a ‘wish-list’ of structural and process factors that contribute to high quality, culturally responsive early childhood care and education.

- Structural factors include funding policies, regulations and curriculum that ensure provision of well qualified teachers, good ratios of teachers to children, small group sizes, and indoor and outdoor environments that are spacious and contain extensive resources for children to explore such as books, music and art materials indoors, and outside space to run and play in trees, gardens, and sandpit.

- Process factors describe the less tangible aspects that are likely to be enabled by having these structural factors in place. For example, central to high quality teaching practices are sensitive, attuned, responsive engagement and in-depth conversations between kaiako/teachers, tamariki/children and whānau/families; recognition and fostering of each child’s particular interests; affirmation of and inclusion of children’s and families’ cultural backgrounds and home languages; and teachers’ capacities for researching and collaborating in their planning, assessment and programme review. Ongoing professional learning opportunities are also important.

- Social justice and equity issues such as accessibility and affordability of high quality early childhood care and education also feature in the students’ concerns.

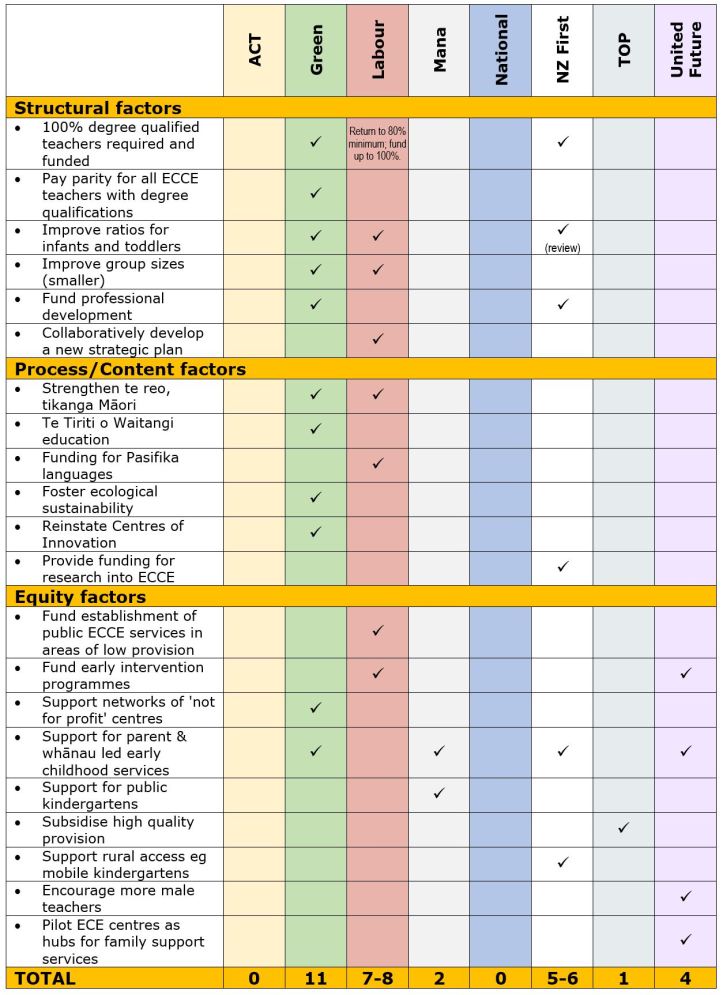

The second part of the in-class exercise involves the students scrutinising the various political parties’ education policies for evidence of a commitment to these features of quality early childhood care and education provision. Lastly, we create a large grid on the whiteboard, with the quality factors listed in a column on the left, and the parties in a row across the top. (See the example at the bottom of this post).

So let’s take a look at the current political parties’ offerings at this point, two months out from the NZ general election. The table which follows the party policy summaries is similar to that produced by students in our collaborative class exercise, but draws in more depth on the latest published policies (August 2017), as when we did the exercise in class several key parties had yet to release their policies.

Parties are listed in alphabetical order.

ACT New Zealand:

The ACT party’s education policy is very brief and focuses solely on their support for ‘partnership schools’, with no mention at all of the early childhood care and education sector. So no ticks for ACT in the table below.

Green Party:

The Green Party has an extensive education policy that includes their vision of an education system that includes a focus on te reo Māori, and on fostering ‘the skills and abilities necessary to create a society that is sustainable, co-operative, inclusive and resilient’. Children and young people are to be supported to ‘participate meaningfully in our communities and learn how to maintain democracy in Aotearoa New Zealand’. Educators are to ‘nurture learners’ dispositions and skills to enable them to lead lives filled with hope, joy and satisfaction’. Education will ensure that children:

- Know the stories of our past and share a sense of national identity grounded in Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

- Learn to solve problems with innovation, creativity and cooperation.

The Green Party not only has a detailed vision, but promises a wide range of specific intiatives, and thus collects a favourable number of ticks in our table (below).

Labour Party:

Labour’s ‘Education Manifesto’ pledges to collaboratively develop another strategic plan for early childhood care and education. Their 2002 strategic plan for ECE had been celebrated for its trajectory towards a fully qualified early childhood sector and pay parity with primary teachers, as well as its emphasis on collaboration with Māori and other parents/whānau and focus on communities of learning.

Labour’s 2017 manifesto focuses strongly on barrier-free access to quality public education, ‘championing quality teaching and the importance of a respected and supported teaching profession at all levels’. Another favourable number of ticks in our table (below).

Māori Party:

The Māori party website did not have an education policy posted at the time of writing.

Mana Party:

The Mana Party’s education policy is a succinct two-sentence statement:

‘A 100% free, high quality public education system to ensure life-long learning, from early childhood to the tertiary level, is the best investment a country can make in its own future. MANA is committed to ensuring the public education system is fully equipped and funded to enable all learners to achieve to their full potential.’

So a lack of specifics, but ticks in our table (below) for early childhood care and education being free and high quality under Mana Party policy.

National Party:

The National Party education policy contains no mention of early childhood. This is not surprising given National’s record of having quickly reduced the percentage of qualified ECE staff from 80% down to a minimum of 50%, whilst proclaiming success at meeting its ‘Better Social Policy’ target of increasing our already-high early childhood participation rates, ignoring the potential damage caused by children’s participation in poor quality services.

The National Party education policy contains no mention of early childhood. This is not surprising given National’s record of having quickly reduced the percentage of qualified ECE staff from 80% down to a minimum of 50%, whilst proclaiming success at meeting its ‘Better Social Policy’ target of increasing our already-high early childhood participation rates, ignoring the potential damage caused by children’s participation in poor quality services.

National has also been content to leave early childhood care and education to the mercy of the market, and the percentage of private, for-profit centres has increased noticeably over the past nine years of National government, whilst public kindergartens have struggled with a funding cap that has resulted in staffing cuts. So no ticks whatsoever in the National Party column (see table below).

New Zealand First:

NZ First’s education policy contains a strong focus on supporting rural and parent-led models such as Playcentre, and on families supporting their own children at home such as via the HIPPY parent programme. It supports returning to the previous Strategic Plan’s goal of 100% qualified early childhood teachers and establishing a fund for researching ECE in New Zealand.

NZ First’s education policy contains a strong focus on supporting rural and parent-led models such as Playcentre, and on families supporting their own children at home such as via the HIPPY parent programme. It supports returning to the previous Strategic Plan’s goal of 100% qualified early childhood teachers and establishing a fund for researching ECE in New Zealand.

The Opportunities Party (TOP):

The Opportunities Party (TOP) has an extensive education policy, though this is light on specifics with regard to early childhood care and education. They see ‘investing’ in early childhood education as a priority: ‘Over time we would like to see high quality, free, universal full-time ECE for children aged three years and over’ via subsidising ‘attendance at licensed high-quality childcare providers’.

The Opportunities Party (TOP) has an extensive education policy, though this is light on specifics with regard to early childhood care and education. They see ‘investing’ in early childhood education as a priority: ‘Over time we would like to see high quality, free, universal full-time ECE for children aged three years and over’ via subsidising ‘attendance at licensed high-quality childcare providers’.

TOP’s policy doesn’t deal with the current issue of high levels of private, for-profit provision in our sector, unlike Labour and the Green Party, who recognise the need to support public provision. There are no further specifics detailed in TOP’s policy, so few ticks for them.

United Future:

United Future, like NZ First, supports in-home and parent-led programmes. In relation to centre-based provision, United Future wants to encourage more men to be early childhood teachers, and has picked up on one of the 2011 ECE Taskforce’s report recommendations for early childhood centres to serve as community hubs, offering parenting courses, budget advice, and health and counselling services.

United Future, like NZ First, supports in-home and parent-led programmes. In relation to centre-based provision, United Future wants to encourage more men to be early childhood teachers, and has picked up on one of the 2011 ECE Taskforce’s report recommendations for early childhood centres to serve as community hubs, offering parenting courses, budget advice, and health and counselling services.

Summary: An indicative table of different policy commitments (August 2017)

The table above shows there is quite a range of different emphases across the parties, as well as divergence with regard to the numbers of specific commitments made. This is perhaps a complicating factor for those who genuinely want to understand the different policy offerings. However, once we have done such an exercise in class, students express how interesting it has been to compare the policies, and that they now feel better positioned to make an informed vote in the forthcoming election.

Our various education sector organisations are providing their own ‘wish-lists’ for other sectors. You may want to explore these further as you prepare to vote this September.

- http://www.voteeducation.org.nz examines the parties’ policies on:

- pay equity for education support workers and teacher aides

- charter schools

- funding review and operations grant freeze

- National Standards

- learning support

- funding for ECE

- top priorities and first 100 days

- http://ppta.org.nz/focus/category/party-policy examines:

- student, teacher and parent engagement in long-term planning for education

- Tomorrow’s Schools

- charter schools

- schools as community hubs

- school class sizes

- per-student funding

- resourcing for students with greater socio-economic needs

- teacher salaries

- teacher professional development

- reducing over-assessment, unproductive box-ticking and red tape

Jenny Ritchie has a background as a child-care educator and kindergarten teacher, followed by over 25 years’ experience in early childhood teacher education. Her teaching, research, and writing have focused on supporting early childhood educators and teacher educators to enhance their praxis in terms of cultural, environmental, and social justice issues. She currently shares the presidency of NZARE with Agnes McFarland.

Jenny Ritchie has a background as a child-care educator and kindergarten teacher, followed by over 25 years’ experience in early childhood teacher education. Her teaching, research, and writing have focused on supporting early childhood educators and teacher educators to enhance their praxis in terms of cultural, environmental, and social justice issues. She currently shares the presidency of NZARE with Agnes McFarland.

Cover photo credit: New Zealand Electoral Commission

This was a very interesting read, thanks. Does going through this process increase your students engagement in the election process? Do more of them plan to vote by the end of it?

LikeLike

Yes the students tell me that they have found the process very useful and that it will help them be clearer about making an informed voting choice. Hopefully they do go on to vote!

LikeLike

[…] 1. Election 2017: Spotlight on early childhood policy (link) […]

LikeLike

[…] #3: “Election 2017: Spotlight on Early Childhood Education Policy” (read it here) […]

LikeLike