Dr Ann Milne, Ann Milne Education

The question in the title to this blog is my usual response to the question I am regularly asked after talks and workshops about Colouring in the White Spaces in our education system. Someone will ask, “How is all this relevant to me when I don’t have any/many Māori children in my school?” My answer is usually met with an uncomfortable silence.

What are White Spaces?

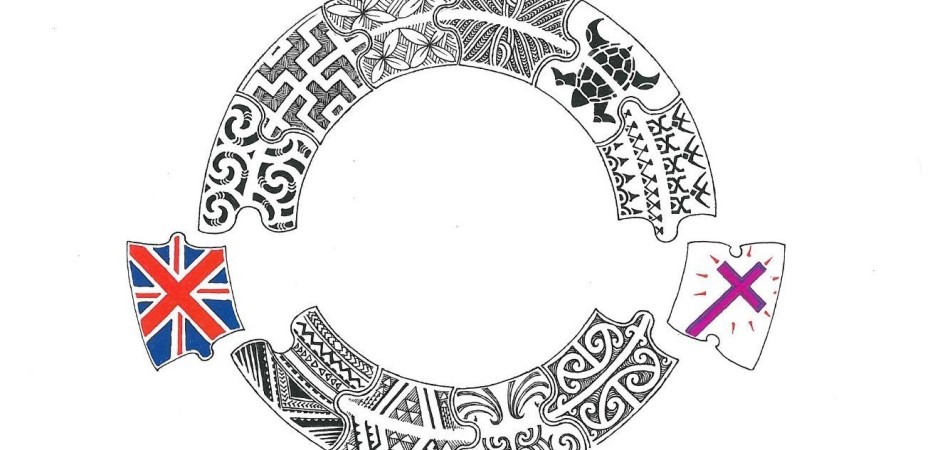

The original artwork (above) was gifted to me by Maori artist and master carver, Blaine Te Rito, to open my doctoral thesis and my book. It is a powerful interpretation of the idea of White spaces. Blaine explains that the circle represents the importance of pre-colonial Māori and Pacific societal structures: education, language, culture, spirituality, and environmental resources. The break in the circle represents the disruption, through colonisation and Christianity, the White spaces that were incurred as a result, and the impossibility of re-completing the circle with pieces or structures that are a completely different shape and are never going to fit. Blaine called the piece Papahueke, which means to be unyielding in the face of this opposition.

Although, internationally, there is a significant body of research on Whiteness and White privilege (for example, see here, here, and here), in Aotearoa New Zealand we have been largely silent about White spaces in our “Whitestream” schools. The racist backdrop that is pervasive in our education system creates and perpetuates the White spaces that marginalise and alienate our Māori learners, yet it is a backdrop that we rarely name as being a problem.

As Pākehā teachers and school leaders, we might not understand this, but when I interviewed senior Māori students in Kia Aroha College about the White spaces they had encountered in their schooling experience, they identified these spaces all too easily. Most telling of all was the comment from a student that goes straight to the root of the problem: “White spaces are everywhere,” she said, “even in your head.”

Changing that space

And that monocultural, Eurocentric thinking “in our heads” is the key space that we need to address, because we each have the power to make that personal change. For too long, the majority of Pākeha in Aotearoa New Zealand have shied away from those words that make us uncomfortable, like White supremacy, White privilege, White fragility, Whiteness and racism. This discomfort is the reason why the second question I’m asked most often, usually by individuals who come up to me after a talk, is why am I using the word, “White.” I ask what word they would like me to use? The inevitable answer is “New Zealander.” One young man, who chased me some distance to make his objection known, added ageism to his racism when he informed me it was a “generational thing” but he and his friends preferred to be called New Zealanders.

Statistics NZ found that when a “New Zealander” category was added as an ethnicity option in the 2006 Census, those who chose it were overwhelmingly from the New Zealand European group. Māori however, have no similar confusion about the difference between nationality and ethnicity, or culture. Penetito explains, “When they think about culture, Māori are likely to be thinking of their identity, their whakapapa (genealogy), which carries with it the notion of determinism”, which includes “notions of biology, genetics, and inheritance, making it equivalent to the concept of race and ethnicity”.

My choice of the word, “White” is a deliberate naming of our unwillingness to see this difference. Kegler calls our use of neutral or more comfortable terms, “the spoonful of sugar that makes the medicine go down.” As she explains, the only people fooled by our “linguistic gymnastics” and “whitesplaining”—that is, by our choice of words we find more acceptable, like “casual racism,” or “unconscious bias”—are White people. There are no degrees of racism, no levels to filter its effect, yet, even when we are faced with hard evidence, as in the racist conversation overheard after a car hire salesperson forgot to end his phone message to my adult granddaughter a few months ago, commenters were reluctant to call racism what it is.

Understanding the pervasive Whiteness in our schools and classrooms is crucial if we want to make change for our Māori and Pasifika learners, but the fact is that in 2017 in New Zealand:

- 73% of all teachers are Pākehā

- 80% of school management and leadership positions are held by Pākehā

- 73% of all teachers are female

Yet the groups our education system fails most consistently are Māori and Pasifika boys, followed by Māori and Pasifika girls. This means there is a huge gap in the understanding of the lived realities of the children we need to make the biggest changes for, and this gap is the real space our professional development needs to target—not how to get better literacy and numeracy outcomes! Unfortunately, this thinking escapes us completely as we are coerced through offers of targeted funding into Communities of Learning to address the perceived deficits in Māori boys’ writing (or Māori girls’ writing, or, Pasifika boys’ and girls’ reading, writing, and maths). I live in hope that the abolition of National Standards and other promises by the incoming government might be a first step in changing these priorities and allowing schools to define their own community, as my recent ULearn17 keynote argued.

So who needs to learn most about White privilege?

People learn about privilege when they don’t have it. As Pākehā, our privilege is accepted as “normal” because we never have to think about it, and this starts from birth. Māori, on the other hand, have had generations of learning about who has power and who benefits from it.

About 12 years ago, I searched high and low for Christmas presents for my twin granddaughters, Kohanga Reo babies from a few months old, who had asked for dolls. I wanted dolls that looked like them. After aisle upon aisle of white, blonde dolls I gave up and ordered two brown dolls online from America. The girls took one look at the brown dolls, then threw them in the corner pronouncing they were “ugly,” thus confirming the famous experiment by psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark with brown and white dolls in the 1940s, and repeated here by a USA high school student in 2006. Using the twins’ thoroughly discarded dolls, a group of Kia Aroha College students repeated the Clark experiment in 2008, with five-year old Māori children in a Māori immersion class, with the same result. If we want to counter the reproduction of these normative beliefs in our children, we need to start early.

We need to teach Pākehā children that there are reasons why, from the moment they are born, due to no conscious action on their part, they are far less likely:

- to be failed by their schools

- to be unemployed

- to live in poverty

- to have poor health

- to be treated unfairly in the justice system

- or to go to prison

The reason we need to teach Pākehā children about privilege is not to make them feel guilt—it is to make sure they do not grow up to perpetuate the situation.

Teaching children the old adage that we don’t “see colour” isn’t helpful, and is privilege in itself. Of course we see colour! Seeing, understanding, and being aware of colour allows us to examine our attitudes and beliefs towards people who are different from ourselves. Being White shouldn’t mean we can remain ‘invisible’ because our culture, our identity, just “is” like the air we breathe. Knowing that our undeserved sense of entitlement and our unacknowledged privilege impact negatively on other people, and can be changed once we understand them, is a lesson our Pākehā children have the right to learn so they can contribute to a more equitable future, and do better than we have done in the past. We are selling our Pākehā children short if we don’t engage them in this learning.

Māori and Pasifika children have the right to the same lesson for different reasons. Without it, they will continue to believe, amplified by our education system, that their position at the bottom of all our statistics is their fault. They have the absolute right to critical, and culturally sustaining pedagogy that gives them the same educational sovereignty as their Pākehā peers—a right to educational pathways “as Māori” that are not reduced to limited, White norms and definitions of “success.” This is the responsibility of all educators and all schools.

Dr Ann Milne is the former principal of Kia Aroha College, a special-character, bilingual, secondary school in Otara, South Auckland. As a Pākehā educator, Ann is a strong critic of pervasive, deficit-driven explanations of “achievement gaps” and Māori and Pasifika “under-achievement.” She led the Kia Aroha College community’s almost 30 year journey to resist and reject school environments which alienate Māori and Pasifika learners, to develop a critical, culturally sustaining learning approach centred on students’ identities “as Māori”, “as Samoan”—as who they are first. Ann’s book, Colouring in the White Spaces: Reclaiming Cultural Identity in Whitestream Schools, was published in 2016 by Peter Lang (New York).

[…] Source: NZARE Te Ipu Kererū – this article has been re-published with permission by the author. […]

LikeLike

[…] 6. Who should learn most about White Privilege – Māori students or Pākehā students? (link) […]

LikeLike

There are Māori children at our school who do NOT identify with being Māori. When I speak with the parents of these children they say that they themselves identify as Māori, but that their children do not. The parents register their children on our school roll as NZ European. I think more should be done to encourage parents to register their children as Māori. I think that these Māori children are being misrepresented in any government data about Māori learners because these children have been ‘whitewashed’. If as a teacher I am unaware that there are Māori children in my class, how can I encourage these children to access Te Ao Māori, AS Māori?

LikeLike

Kia ora Sarah – thanks for your whakaaro 🙂 You might also be interested in this recent article which critiques the way that learners are classified into ethnic groups for statistical purposes – e.g. students who identify as both Māori and Pāsifika get classified as Māori; students who identify as Asian, Pākehā and Pāsifika get classified as Pāsifika etc. With so many NZ residents/citizens having mixed heritage, this is another issue in how children are represented and how ethnic groups are perceived in national statistics etc. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40841-017-0089-9

LikeLike

Kia ora Sarah. Thanks for your comments. Your experience is a common one. I have two thoughts about the reasons why. One is that firstly, we have to give our Māori children a reason to want to be seen as Māori at school. For many of our children, it’s just really hard work to have to go against the flow of what is “normal” in the school environment and it is just easier to try to fit in. That leads to my second thought – James Banks has a typology http://www.ascd.org/ASCD/pdf/journals/ed_lead/el_197612_banks.pdf, which is still relevant. He proposes stages of identity development, which are not clearly defined, and obviously overlap. The first stage is the one you describe, where young people take on all the negative stereotypes about their ethnicity and often reject that identity. The key idea is that it is a stage, which children move through, like most developmental stages, if the environment supports that development.

LikeLike

[…] #10: “Who should learn more about White Privilege – Māori children or Pākehā children?” (read it here) […]

LikeLike

[…] example of “colour-blindness” or “naïve egalitarianism” where difference and diversity are ignored in a philosophy that promotes seeing everyone as the same. Ms Jones later said, “… maybe […]

LikeLike

[…] We must change– transform– how we think and what we do. Recognising the non-neutrality of the dominant culture and its impact on the structures of schooling is intertwined with the belief that those structures […]

LikeLike

[…] education system. The pre-service teachers saw these effects through, for example, classrooms being white spaces, and non-Pākehā whānau facing challenges in engaging with schools. The participants’ […]

LikeLike