Professor Mere Berryman, University of Waikato

Having to leave our culture at the school gate to achieve in schools that marginalised and belittled our own cultural identity has been the experience of generations of Māori students, including myself.

Regrettably, especially for Māori boys not prepared to compromise their cultural identity, many were forced to fit within a schooling system that held little promise for their future. As a result, too often these students were described as having ‘fallen through the cracks.’

I would suggest this was no mere accident.

Assimilation is the systematic redefining of students’ identities, so that they are forced to fit into the culture of the majority group. The combined loss of the potential of these young people, over generations, has been enormously wasteful and continues to be costly for our country.

Education without compromise

Rethinking and redefining education so that Māori students are able to receive education without having to compromise their own cultural identity was finally to see the emergence of the Ka Hikitia school policy. First released in 2008, this policy direction, and the Education Review Office’s 2017 evaluation framework, aim to promote equity and excellence ‘as Māori’.

These solutions have emerged over the last 20 years from Māori communities, classrooms and schools, and from the education system itself. Finally, educators in New Zealand’s schooling system have begun to modify the dominant power structures in education in search of students’ rights to the benefits from education promised to both Treaty partners under the Treaty of Waitangi.

However, are we as a nation ready for this?

The call for change

Phase 3, the renewed iteration of Ka Hikitia with three priority statements, was released in January 2018 calling for:

- sustained system-wide change;

- innovative community, iwi and Māori-led models of education provision; and

- Māori students achieving at least on a par with the total population.

At the same time, the New Zealand Schools Trustees Association (NZSTA) and the Office of the Children’s Commissioner (OCC), identified yet again what Māori students told us in 2001.

Alarmingly, this time, it is not only coming from Māori students; the voices of immigrants and refugees are also asking us to understand them and their whole world. Together, students speak of the ongoing racism they continue to face. Ongoing evidence of inequity for Māori is still stark. I wonder, will our refugee students become our next shameful statistic?

While the change required is complex, we now have the evidence to show what works. We have built on learnings since Te Kotahitanga and we now know how to accelerate the difference and work seamlessly with primary schools. Alignment of coherent principles, theorising and practices, across schools, communities and society is essential. This will not be solved by a one-off, one-group programmatic approach; alignment and coherency are essential.

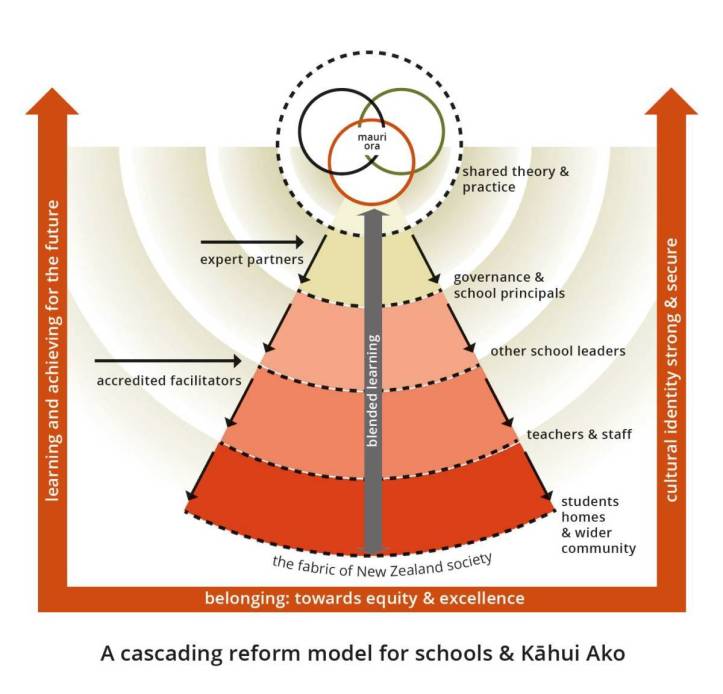

Poutama Pounamu have seen what can be achieved when school leaders understand and follow a theory of change (see figure below) that has been informed by New Zealand research. Together, with facilitated support, working systematically to reform education through across school and within school teachers has added immensely to these benefits.

When Kaiwhakaako* are also a part of the same critical learning and reform conversations, and they are spreading learning to new members from across the whole community, the effect is further spread and accelerated. Kaiwhakaako challenging themselves to be agentic at a personal level has led to new understandings of the part they have played in supporting a system that’s actually been inequitable, particularly for Māori learners.

School and community members who engage in this conscientisation can begin to ask critical questions of themselves and others about what needs to be done differently. Now that they understand how power and privilege are playing out, they can begin to engage in resistance.

When we engage in new practices that focus more on equitable social reality for Māori learners, transformative praxis has begun. Rather than feel they must fit in, Māori students can truly belong.

As a nation, we must make the difference, our students are our future.

We must all take joint responsibility to engage in reforming education by relearning from the injustices of our collective past and being prepared to share power and work for reciprocal benefits. This must continue to occur within an iterative process that seeks to understand through the voices of the people themselves. It is only then that the change for social justice can finally begin to emerge.

*Kaiwhakaako is the term given to those who are leading their own, and others, learning in Poutama Pounamu’s Blended Learning initiative.

This post was originally published on the Poutama Pounamu website. It is reproduced by permission. A recording of Professor Berryman’s inaugural professorial lecture, which further develops the themes discussed in this post, is available here.

Professor Mere Berryman spent more than twenty years as a classroom practitioner before moving into educational research roles. Her research combines understandings from kaupapa Māori and critical theories and she has published widely in these fields. In 2016, Mere was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to education and to Māori in education. Mere directed both the Te Kotahitanga and Kia Eke Panuku initiatives and now leads the Poutama Pounamu research and professional development group at the University of Waikato.

Professor Mere Berryman spent more than twenty years as a classroom practitioner before moving into educational research roles. Her research combines understandings from kaupapa Māori and critical theories and she has published widely in these fields. In 2016, Mere was made an Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit for her services to education and to Māori in education. Mere directed both the Te Kotahitanga and Kia Eke Panuku initiatives and now leads the Poutama Pounamu research and professional development group at the University of Waikato.

[…] 9. ‘Forced fit’ or belonging as Māori? (link) […]

LikeLike